Reflections on being a Foundation Doctor in the NHS: advice for new FY1s

My perspective on an incredibly daunting, exhausting but rewarding two years that has changed my perspective on what being a doctor truly means.

The last two years has truly flashed by. I still remember my first day as a doctor. I was filled with anxiety, fear and a deep sense of imposter syndrome, whilst sat within the expanse of one of the most highly specialised hospitals on the planet. It was a feeling I’d never experienced previously because at university you were shielded by that badge on your shirt that signalled to everyone around you that you were ‘just a medical student’ and only there to watch and learn, not actively participate in patient care. Unfortunately, there’s no hiding in Foundation Years, you either sink or swim.

In this article, I outline a few things I’ve learnt along the way. I’m hoping my experience can help someone else who may also be in the same position that I was two years ago.

Ask for help as often as you need

It’s completely normal to be apprehensive about starting a new job, especially when it’s the first day of being a doctor!

To go from virtually no responsibility at university to being responsible for around 100 patients overnight is a major step up. Add to this that many new doctors may never have had a job before, then the apprehension is not only rational, but understandable.

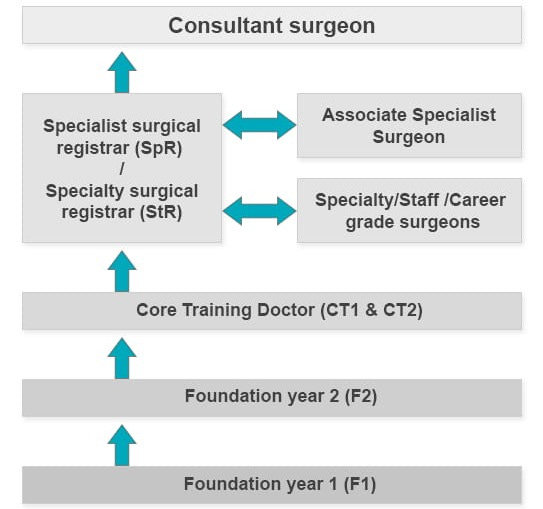

Having just finished finals, it’s likely that your knowledge base is robust but you’ll inevitably work slowly at the start as you get used to your unique departmental environments. My first bit of advice is to ask for help from the established members of the MDT. For instance, when I started my role on General Surgery, I worked with several brilliant senior doctors, ACPs (Advanced Care Practitioners) and nurses who were able to point me in the right direction with a variety of aspects of working. This included being efficient with clinical note taking, completing discharge letters and finding equipment for taking bloods and cannulating. Usually, if you’re worried about a patient, no senior clinician should ever belittle you for asking for advice. Seniors are aware that you’re new to the system and will be willing to help you.

If you’re unsure even 1%, it’s always better to ask a senior than to risk causing patient harm.

I remember one of my first ever on-call shifts, I had a severely co-morbid patient with symptomatic fast AF (for those non-medical, this was very much a medical emergency). I immediately did a basic assessment, but I was really unsure which drug to administer to bring the heart rate down as the patient was already on a variety of cardiovascular medications. One phone call to the medical registrar, whose name I still remember to this day, and the patient had been stabilised and I was feeling far more comfortable in myself. Seniors are there for a reason and are (usually) more than happy to help!

Tough moments are inevitable

Working in the NHS means you see things that non-healthcare professionals never see.

The hardest moments sometimes come when you least expect it and it’s sometimes incredibly challenging to prepare for these scenarios.

For instance, the rapid and fatal global spread of COVID-19 sent shockwaves through the NHS and took the lives of thousands of people. Death, unfortunately, is a certainty when working in hospitals. Different people process this in different ways, but what’s important to know is that you’re never alone in situations where a patient has passed away. I have found that members of the MDT usually provide a robust and empathetic approach to de-briefing that has helped me substantially to process my thoughts after such an occurrence.

We’re programmed at Medical School to think that we cannot make mistakes, but this is also a certainty when you enter the world of the NHS.

In a 2020 BMJ report, it was found that more than 237 million medication errors were made every single year. The key is to be forthright when you’ve made an error and communicate it clearly to your team and the patient. It has been found that most patient complaints stem from poor communication, thus a conciliatory and compassionate approach that communicates mistakes clearly can enhance the patient-doctor relationship significantly.

The electronic systems will (most likely) drive you mad!

As quite a tech savvy person myself, I found myself cursing at the very technology I worked with day-to-day more than I would have liked.

What do you mean it takes 5 minutes to load each of the individual patient notes, whilst the consultant stands there impatiently tapping his feet before a 40 patient ward round?!..

This is one of the major issues that still persists within the NHS. There is a paucity of high-quality electronic patient systems that are well integrated with electronic prescribing and external GP records. It’s 2025 for heaven’s sake, but this will undoubtedly still be the case in 2050 (if the NHS survives that long). Especially in my FY2 year in Harrogate, I found that my operational efficiency dropped significantly when compared to working in Leeds as the systems were far slower. Moreover, it was basically a lottery at times as to which computers actually worked. The labour ward, for instance, had about 8 laptops with only about 3 functioning at any one time. Laughable.

There’s no easy way to get slicker at using these systems other than lots and lots of practice. If you’re going to do any e-learning prior to starting your on-call shifts, then the electronic patient system tutorial is the one to do first!

It’s worth accepting that you’ll be slow for the first month or so, but don’t stress because your senior colleagues will be extremely understanding. If you’re lucky enough to be working in a trust with PPM+ or EPIC, then you’ll fly… if you’re in a trust that’s clinging onto paper notes, well then… my sincere condolences.

Make an effort with your work colleagues

This is probably one of the most important aspects of working in the NHS.

I’m a big believer in ensuring that you cultivate the environment with your colleagues that you want to work in everyday.

I found that, especially in my FY2 year, I really enjoyed going to work (most of the time!) because it felt as though everyone was friendly, most people knew each other and colleagues were never reticent to give you advice when you were struggling.

I made it a mission to try and learn the names of the people I worked with, where I could. There’s countless evidence to show that getting someones name right fosters an inclusive environment that recognises a colleague’s identity and makes them feel seen. It helps build stronger relationships, enhances communication and has been shown to boost teamwork and morale. It doesn’t matter if it’s the consultant, the ward clerk, the nurse in charge or the ward porter… learn their names if you can! I’ve found that making this small effort can go a really long way, because when you inevitably need help on the ward, then a robust working relationship with your colleagues can really bail you out… trust me!

And finally, perhaps my most important bit of advice, make the most of social opportunities where you can.

This made the entire experience of foundation years immeasurably better and can really help you strengthen the relationships you find at work into friendships that endure beyond the 2 years. I would honestly say the people you surround yourself will be the main determinant of how much you enjoy these initial two years of work. On this positive note, here are a few of my favourite pictures from a wonderful two years with just a few of the fantastic colleagues I had the pleasure of working alongside!

You’re in a privileged position - embrace the opportunity!

It’s estimated that less than 0.2% of people in the world are doctors. This is an incredibly privileged and unique position to be in. With this however, comes a significant responsibility. Patients trust you with things that they don’t even trust their partners or family members with. It’s important to have an awareness of this and ensure you always keep the best interests of the patient at the heart of your work. Communication, compassion and honesty is key to this. If you embrace those core values, you will excel.

One final thing. It’s a certainty that you’ll have some really good days, but you’ll also have days that make you question why you chose this career. When it comes to those lows, I fall back on one big concept: ikigai.

As you can see, being a doctor allows you to be remunerated for your work (perhaps insufficiently, as outlined in my previous article below) and is a profession the world undoubtedly needs (ill health costs the UK economy alone roughly £132 billion a year).

The last two aspects are deeply personal, and will vary from doctor to doctor. Personally, I feel as though I do a somewhat decent job, but that it’s also a career I have profoundly enjoyed so far. Yes, there are several frustrations with the role that I’m sure I’ll talk about later on, but ultimately I don’t think there’d be many other jobs out there that provide quite this sense of purpose.

My advice to anyone just starting out would be to walk into it with an open mind, embrace it and immerse yourselves in the path ahead. I wish you the very best of luck!